Towards A Smart Digital Forensic Advisor To Support Triage

–

Valeria Minero Abreu (UCL), Catherine O'Brien (UCL), Mark Warner (UCL), Maria Maclennan (University of Edinburgh), Niamh Nic Daéid (University of Dundee), Oriola Sallavaci (University of Essex), Sarah Morris (University of Southampton) and Alessia Stroni (University of Essex)

ESRC (ES/Y010647/1)

Metropolitan Police Service, Nottinghamshire Police Service, West Midlands Police Service, College of Policing and Forensic Capability Network

Send us your feedback

We are interested in how you view our findings, and where you may have used our findings to influence your thinking, or your practice. Please fill out this short form to share your feedback: Feedback form

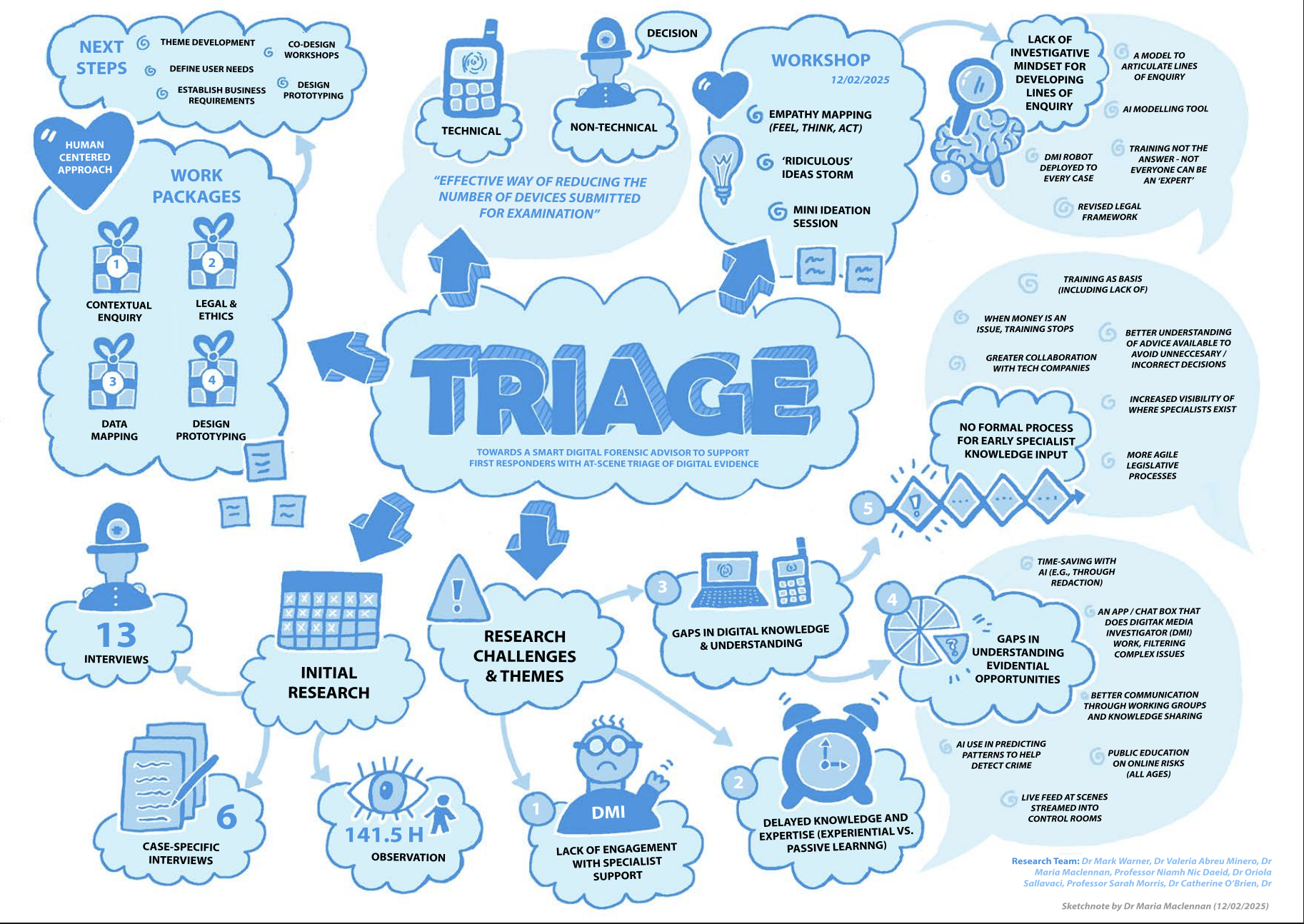

This project aims to lay the foundations for the development of a smart digital forensic advisor for first responders to help them apply a consistent and evidence-based approach to performing digital evidence triage at-scene. We will explore existing practices, resources, challenges, and user needs around the process of search and seizure of digital devices across two distinct crime types. Through this, we will identify data that could be used to inform the smart advisor tool, and data gaps that the tool itself could address. We will also be exploring both the legal and ethical implications of its use, due to the tools potential in helping to shape decision-making at scene. Finally, drawing on our findings we will develop a set of early-stage low-fidelity prototypes to present back to our user groups.

Why are we doing this research?

- With the proliferation of technology within our society, it is unsurprising that over 90% of reported crime has a digital element.

- The increase in technology use to commit crime (e.g., cybercrime) or to facilitate criminality (e.g., the use of a mobile phone to organise an offence), presents forensic and investigative opportunities.

- As device use within criminality has increased, so too has the number of devices that are being seized and are subsequently being submitted for examination to digital forensic labs, with estimates in 2022 suggesting that the backlog of devices waiting to be examined is as high as ~25k devices.

- A 2022 report by HMICFRS states how approaches to identifying, seizing, and examining digital devices must become more sophisticated. In this same report, digital triage is suggested as an effective means to reduce the examination backlog identified.

- While many police organisations use triage, little is known about how triage is applied across and within forces, where the pain points are around effectively applying triage in practice, and where opportunities exist to support triaging practices with emerging technologies.

Main findings

Current findings suggest different forms of digital evidence triage are occuring at different stages of an investigation, including search and seizure planning, at scene search, and post search. A summary of our main finding are:

- “Digital device triage” occurs at multiple stages (at scene, post-seizure, and at submission for examination), each providing key opportunities to focus efforts, prioritise, and reduce unnecessary submissions.

- Improving digital device seizure and handling at the scene depends on creating effective feedback loops across policing, such as showing officers how early actions affect evidential outcomes.

- Hands-on and embedded learning (i.e., experiential learning) that is presented to users where it is contextually relevant, can help increase effectiveness of awareness raising initiatives, and build confidence in digital decision-making,

- Effective digital evidence submission depends on meaningful collaboration between investigators and digital specialists, focusing on how devices relate to the investigation.

- Embedding digital expertise early in investigations strengthens collaboration between officers and specialists, turning digital support from a reactive service into a core part of investigative practice.

- Leadership plays a crucial role in shaping digital practice, as visible engagement from managers who prioritise device triage, preservation, and early digital input signals that digital evidence matters and drives cultural change across policing.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help bridge the gap between the growing demand and limited specialist capacity for support with the increasingly digital focus of investigations.

- Broad seizure powers in the legislation facilitate “seize all” practices; better understanding of and adherence to the legal criteria of proportionality and necessity is essential and should be reflected in training, guidance and operational tools.

- Modernising legislation to reflect cloud-era realities would provide clarity for officers, would promote proportionality and protect individual rights.

Collaborative Digital Device Triage Practices in Policing in the UK

- Persistent gaps in digital understanding: Significant digital knowledge gaps remain across frontline officers and investigators, particularly in understanding how to assess device relevance at-scene and what different digital devices can yield.

- Lack of confidence contributes to ‘seize all’ approach: Limited digital understanding at the point of seizure drive risk-averse decisions and perceived safety in over seizure to avoid missing evidence, pushing triage decisions further up the investigation chain.

- Inefficient device submission practices: At the submission stage, poor digital awareness results in inappropriate or ill-informed examination requests, leading to rejections, rework, and delays in investigations.

- Passive training has limited impact: While forces have introduced training sessions, guides, and awareness materials, these passive, frontloaded approaches have struggled to meaningfully improve digital competence or confidence.

- Specialist support exists but is underused: Digital Media Investigators (DMIs) and digital forensic specialists are available across most forces, yet their support is often overlooked or misunderstood, with many officers unaware of how or when to engage them.

- Informal engagement generates incidental learning: When investigators do interact with digital specialists (e.g., during returned submission or advice calls), these moments create valuable incidental learning, in line with policing experiential learning culture.

- Early specialist input prevents missed opportunities: Specialist advice typically enters the investigation late (i.e., after device seizure or during submission) leading to lost data and missed evidential opportunities. Formalising early involvement, such as at the point of crime scene management, would improve preservation and focus.

- Technology-facilitated experiential learning as potential for scaling: Tools like live-streaming via body worn video (BWV) and enhanced submission systems can provide real-time guidance, mirroring ‘over-the-shoulder’ learning. Emerging AI systems (LLMs, Machine Vision) could scale this support, though ethical safeguards are essential.

- Shift from passive to experiential learning: Existing digital triage systems already foster incidental learning. Future strategy should deliberately embed these experiential opportunities into everyday workflows to create sustainable digital capability.

Implications

- The absence of structured feedback loops prevents organisational learning. Introducing mechanisms to embed early digital input into an investigation would improve practice consistency and reduce missed evidential opportunities.

- Gaps in understanding digital opportunities, specialist capabilities and available support as well as communication barriers between investigative and digital teams hinder effective device triage decisions. Building structured, consistent and formal communication channels would help integrate specialist advice earlier and more effectively.

- Traditional passive approaches to digital training have limited impact. Embedding learning opportunities into existing working practices and use of systems as learning environments will enable officers to build competence through action, in line with policing’s experiential learning culture.

- Hierarchical structures within investigations often override digital specialist input. Digital input should be a required step in early investigative planning, not an optional add-on. Mandatory structured engagement with digital specialists at seizure or other device triage points would help prevent missed opportunities, over seizure and inefficient submissions.

- Critical opportunities to preserve volatile data are often lost because of inconsistent, contradictory or lack of digital handling guidance. Integrating preservation and handling advice into the search strategy, initial direction from supervisors (or via control room direction) would reduce data loss, support informed decision-making and improve evidential integrity.

- Cultural change requires visible buy-in (endorsement) from senior leaders and supervisors. If digital considerations are consistently prioritised in leadership messaging, planning, briefings and strategies, they will become embedded as default practice.

Developing impact

- The use of co-design methods as part of this research has influenced thinking around the design of processes, such as device submission. These methods have highlighted the need to collaborate in the design of systems and processes, to ensure the views of different users and stakeholders are heard and considered.

- Our findings on the need to develop experiential and context-aware training around digital aspects of investigations that aligns with the “learning on the job” policing culture, have directly influenced the design of training inputs within one police service. Drawing on our findings, they have transitioned from “presentation-heavy sessions” to an “immersive experience where students investigate a constructed scenario that guides them through digital forensics, telecoms data, and standard investigative routes”. Moreover, other police organisations are interested in this approach, and on the advice of the Digital Investigations Advisory Group at the College of Policing, it has been submitted to the Practice Bank to help other forces replicate the practice.

- The Triage event launch report (2024) was cited in the Westminster Report on Forensic Science in England and Wales: Pulling Out of the Graveyard Spiral (2025).

Reports

O’Brien, C., Abreu Minero, V., Warner, M., Maclennan, M., Morris, S., Nic Daéid, N., & Sallavaci, O. (2024). Digital Forensic Triage Project Launch Event Report.